Part Two: Diphtheria in Mt. Washington and the Henry Archer Langdon Family

When I first started volunteering at the cemetery 30 years ago, I would often stop at a row of graves near the fountain and contemplate the tragedy that must have befallen this family. Each headstone lists only a name, birth date and death date, but those deaths happened over such a short period of time. The father passed away at the age of 36, having outlived his wife who died at the age of 31. His wife had given birth to five children. Only one of the five children lived past the age of five. Here is what is written on the headstones:

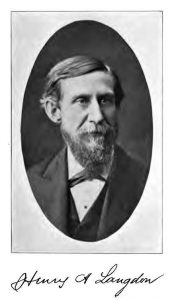

Dr. Henry Archer Langdon Born  May 28, 1839, Died May 13, 1876

May 28, 1839, Died May 13, 1876

Emeline Langdon Born Dec. 31, 1842, Died July 8, 1874

Chester Stebbins Langdon Born Sept. 5 1867, Died July 20,1868

Thomas Langdon Born June 22, 1874, Died Oct. 4, 1874

Anna Dawson Langdon Born Sept. 9, 1870, Died Oct. 20, 1874

Clara Langdon Born May 5 1869, Died Dec. 7 1874

I would periodically scour the Internet for information on the father’s name, Dr. Henry Archer Langdon, to no avail until nearly ten years ago. Now you can find much more on the Internet when you search his name, but back then, one of the few documents I found was truly a find: Dr. Langdon’s older sister, Harriet, wrote a diary about her family and about growing up in Cincinnati. It was published for private distribution in 1908 when Harriet was 83 years old.

In Part One of this installment, we explored the nature of diphtheria, one of the dreaded diseases of the 1800s and early 1900s, a disease that caused the death of many of those buried in the Mt. Washington Cemetery. If you’d like to read that post, please scroll back to December 6, 2016. Two of Dr. Langdon’s four children died of diphtheria, Anna and Clara. Before those tragedies struck, however, Dr. Langdon had already lost his firstborn child, his wife, and one of the twin sons to whom his wife had given birth.

Dr. Langdon was no ordinary doctor. He was an exceptionally gifted one who had experienced some of the best schooling and training of his day. Before his untimely death, he had treated and healed countless of the afflicted, which must have made it all the more frustrating and heart wrenching to be unable to heal his wife and children when they fell ill.

His sister described Henry in her diary: “In childhood he was timid and dependent, not indicating the strong, brave nature that characterized his manhood. He was fond of home and home pursuits; the innocent pleasures of country life had a charm for him.” “He grew tall, slender and delicate looking, fair with light hair and clear blue eyes like our mother’s and a pleasing expression of countenance that he retained through life.”

“He early showed a predilection for the science of medicine. Our mother endeavored to dissuade him from choosing the profession, fearing his physical strength would not be equal to the hardships of a physician’s life. But her objections gave way when she saw he had chosen because of his love for the profession.”

“He began his medical studies in the office of Doctors Elstun and Nixon, at Tusculum (Columbia). He entered Miami Medical College in Cincinnati, attending the course of lectures, etc., graduating with honors, a position being given him with the faculty as “Demonstrator of Anatomy.”

“On the breaking out of the Civil War he endeavored to get a position as surgeon in the army. The Board of Medical Examiners was located at Columbus. When a call was made for surgeons brother Henry went to Columbus to be examined with other applicants. His youthful appearance, however, was against him. The Board refused to examine him and he came home much chagrined that not even a chance was given him. In the course of a few months another call was made for surgeons, and Henry again went to Columbus and this time was more successful. Dr. John Murphy of the Miami Medical College was one of the examiners and when someone made an allusion to the youth of the applicant, Dr. Murphy remarked, “I know him. Give him a trial.” The youthful applicant surprised some of the members of the Board with his knowledge. The examinations were very strict, but there was not a question, written or oral, that he was unable to answer correctly. He was given the necessary credentials and returned this time well satisfied over the outcome.”

Dr. Langdon served for 3 years as a surgeon in the 79th Ohio Volunteer Infantry until the end of the war in 1865. In 1862, he began his service as First Assistant Surgeon to Dr. Elstun, was promoted to Head Surgeon within a few months, and was made Brigade Surgeon shortly thereafter. He was with General Sherman’s Army in the Atlanta campaign and the March to the Sea.

Upon returning from the war, Dr. Langdon “formed a partnership with Dr. Elstun and commenced the practice of medicine in Columbia. He was a successful doctor and speedily rose in his profession,” Harriet wrote. Dr. Langdon practiced medicine in a small office on Eastern Avenue in Cincinnati. That medical office now resides at Heritage Village Museum in Sharonville.

As Henry’s sister writes, “After his marriage he bought Dr. Elstun’s home and also his interest in the practice. To have a home of his own after years of wandering was happiness itself. He was devoted to his family, almost idolized the two little daughters. But this happiness was as brief as it was beautiful. Only a few years passed before crushing sorrows came in quick succession. In four months the wife, one of the twin babies and the two little girls passed out from the home never to return.”

We can only imagine the heartbreak the family endured over such a short period of time. Henry and Emeline’s firstborn child, Chester, died at nine months of age. I do not know of what. Emeline gave birth to twin boys, Thomas and Willie, on June 22, 1874. Emeline survived the birth by little more than two weeks, passing on July 8, 1874.

Her death record shows that she died of puerperal fever (also called “childbed fever”). We now know the fever was brought on by a streptococcal bacterial infection of the uterus or genital tract during childbirth. In those days, doctors and midwives went from patient to patient, unknowingly carrying bacteria on their instruments and on their unwashed hands. Puerperal fever was the single most common cause of maternal mortality in this time period, accounting for about half of all deaths related to childbirth, and was second only to tuberculosis in killing women of childbearing age. It affected women within the first three days after childbirth and progressed rapidly, causing acute symptoms of severe abdominal pain, fever and debility.

We must remember that these deaths were before germ theory was understood. It wasn’t until the 1870s that Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch showed how microorganisms caused disease. It would be another twenty years before the specific bacteria responsible for the most dreaded killers were identified: typhoid, leprosy, and malaria in 1880; tuberculosis, 1882; cholera, 1883; diphtheria and tetanus, 1884; plague, 1894; and dysentery, 1898. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that the importance of hand washing and instrument sterility was accepted and implemented.

The death of one of the twin boys, Thomas Langdon, nearly two months after his mother’s death, may have been hastened by her passing. Thomas’s death record shows that he died of cholera infantum, which was a major cause of infant death in the late 1800s. Cholera infantum was an acute infectious disease of infancy characterized by bouts of diarrhea. A feeble pulse, shriveled, cold skin, sunken eyes, stupor, and coma followed these bouts. Death usually occurred within three to four days, but sometimes within only twenty-four hours of the onset of symptoms. It was a non-contagious disease of young children who had been weaned from the breast and it occurred chiefly between the months of April and October.

A contaminated milk supply was commonly responsible for the disease. Milk was generally collected at dairy farms and transported to the cities by horse-drawn carts. By the time the milk arrived in the cities, it had traveled long distances without refrigeration and was often sold in containers contaminated with dirt and other bacteria. Furthermore, the milk sellers often added contaminated water, salicylic acid and yellow dye to the milk. The water made the milk go further, the salicylic acid was added as a preservative, and the yellow dye was added to make the milk look richer, as though it contained cream. Cholera infantum affected only babies who were not exclusively breastfed.

Only 16 days after Thomas died of cholera infantum, Dr. Langdon lost his 4-year-old daughter, Anna, to diphtheria. As described in Part One of the Diphtheria post, the disease is caused by a bacteria that is transmitted like the common cold, through coughing, sneezing, or from touching a contaminated object. The bacteria produce a toxin that kills the cells of the respiratory pathway, forming a membrane that can close the airway, causing the child to suffocate to death. Six weeks after Anna’s death, 5-year-old Clara, passed away, also from diphtheria.

In Harriet Langdon’s book, she describes the scene of Clara’s passing: “The night the last daughter passed away despair with raven wings settled on the home. I shall never forget the scene as I entered the room – the child lying on the operating table where an effort had been made to relieve her sufferings by an operation for tracheotomy, the doctors standing around, my brother sitting by the fire bowed down with grief. I put my arms around him and pressed my lips to his hair – I could not say a word. I was dumb before such grief.”

Harriet described the time following the deaths of Henry’s wife and four children: “Leaden-footed passed the days, weeks and months, that to my brother seemed like ages…In time hope returned, the clouds drifted away, the skies were blue, and my brother bravely took up the tangled and broken threads to begin life anew.”

In December 1875, Dr. Langdon married Sydnie Edward, and she became William’s mother. Harriet wrote, “He re-established the home with a loving companion and little Willie, the only child left to him. He was young and it seemed as though years of happiness were in store for him. But it was not to be. The poor, tired, overstrained brain gave way in a ruptured blood vessel; after weeks of suffering he peacefully passed away.”

Just five months after their marriage, Dr. Henry Archer Langdon passed away from a brain hemorrhage on May 13, 1876.

…Researched and written by Julie Rimer, January, 2017