THE FOUNDING OF THE MT. WASHINGTON CEMETERY IN 1855

Here is a quote from Stephen Smalley*, prominent local historian, in a book he wrote about Mt. Washington: “The Mt. Washington Cemetery was founded in 1855 by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Dove Lodge 234, a fraternal organization. The IOOF purchased an eight-acre lot from Stephen Davis Corbly, grandson of the pioneer Baptist preacher, John L. Corbly. When the villagers learned of the plan to establish a cemetery, they set up a howl fearing it could be a source of disease, but Dr. Leonard W. Bishop, a respected physician of the village and member of the lodge, assured them there was no hazard.”

I always wondered why Dr. Leonard Bishop had such clout with the people of Mt. Washington, enough to assure them that a cemetery, which was dreaded in the age of cholera, should occupy a place in the heart of the village. At the time the Mt. Washington Cemetery was established, “miasma theory” was widely believed. This theory held that a “miasma,” a noxious form of bad air, spread diseases such as cholera. People believed that unpleasant smelling, rotting organic matter could spread disease. This fear included concern about cemeteries where the bodies of people who had died of cholera were buried. The cadaverous appearance of gravediggers was attributed to the miasma that escaped from coffins. There were even some academics in the early nineteenth century who suggested the theory extended to other conditions as well. For example, they theorized that one could become obese by inhaling the odor of food.

This was a time when cholera’s infectiousness was denied by accepted authorities. In general, cholera was blamed on an assortment of scapegoats: miasmas, filthy living conditions, and on poorer members of society, African Americans and Irish people. The religion of the Irish immigrants in the 19th Century (Catholicism) was especially troublesome to some. There were those who blamed the cholera epidemic on these populations as being the just wrath of an angry God.

During the 19th Century, sanitation was casual. Drinking water was either dipped or pumped from shallow wells, rivers or lakes. Water sellers carried water drawn from wells or rivers. Sewage was deposited by individual households in streams or in cesspools, which were allowed to overflow or seep into nearby sites. Water sources and sewage disposal were positioned for convenience, not safety – often so close together that the odor and taste of drinking water was a problem.

The cholera experience is often considered as separate epidemics – 1832, 1849, 1866, and the late 1870s. In the 1849–51 outbreak, some of the worst hit cities were Cincinnati (5,969 residents died), St. Louis (which lost 4,557 citizens), and Detroit (where 700 perished). In each outbreak, deaths totaled 5–10% of the population. In reality, the boundaries of the outbreak were not so sharp. Cholera killed many between the years cited as epidemics. Further, nothing had been learned about the disease, its prevention or its treatment between the 1832 and 1849 episodes. The only real differences were that by 1849 the populations were larger and transportation was more rapid and less dependent upon water routes. Thus, cholera moved with greater ease to more people.

Gradually, scientists and physicians gave up miasma theory in the late 1800s, particularly after the 1861 publication of Louis Pasteur’s Germ Theory and Its Application to Medicine, which explained that germs, not miasma, caused specific diseases. However, even into the late 19th Century, many held a belief in both germs and miasma. One influential tract on burial customs, written in 1881, paid homage to Pasteur’s germ theory, but the author still found it necessary to warn his readers that corpses gave off gases that were fatal if breathed in concentrated form. The tract informed its readers that, even if extremely faint, the nauseating odor of a decomposing corpse could lead to chronic indigestion and any number of other debilitating illnesses. With the gradual acceptance of germ theory, fear of contagion emanating from a smelly corpse was transformed into a more terrifying fear of invisible germs that could reside anywhere and not be detected.

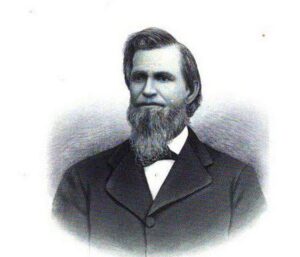

Let’s return to Dr. Bishop who helped quell the fears among Mt. Washington citizens of locating a cemetery in their midst. Dr. Leonard W. Bishop was one of the most notable citizens of Mt. Washington. He was the son of Preston and Anna (Whitaker) Bishop and was born July 25, 1823 in a primitive log cabin on this parents’ farm in Cheviot. Dr. Bishop was one of ten children. He was described as being “of good revolutionary stock and Welsh and Scotch-Irish descent.” His parents were members of the Presbyterian Church. His father was an old-line Whig in politics who followed a seafaring life as a captain. When Leonard was two years old, his family moved to Cincinnati for six years before relocating to a farm near Goshen in Clermont County, where his parents lived until they both died in 1864.

For the brief time he was in Cincinnati, Leonard attended a primary school. However, after his family moved to Clermont County, Leonard labored on his family’s farm until he was 17 years old. He furthered his education by studying on rainy days, as well as during the mornings and evenings. He also periodically attended a common country school during the winter months. When he was 17, he began attending a select school taught by the Reverend L.G. Gaines known as the “Quail Trap Academy.” In this school, many men who later became distinguished in professional life received their education. At nineteen years of age, Leonard began teaching while continuing his studies. Later, he took some courses at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and began studying medicine with Dr. Colon Spence of Perin’s Mills, an area of Clermont County. He taught school and continued his medical studies until he was twenty-five years old, at which time he attended a course of lectures at the Ohio Medical College.

He then went to Mt. Carmel, Ohio, to form a partnership with Dr. Frank Parrish. In the summer of 1845, he received the three symbolical degrees of Free Masonry at the Goshen Lodge, F. and A.M., No. 119. He remained in Mt. Carmel until the end of June 1849. At that time, the Asiatic cholera was rampant in the country and was particularly malignant in the neighborhood of Wineburg in Anderson Township, Hamilton County. Due to the need for medical help there, Dr. Bishop relocated and gained a large practice and deserved reputation. This period established him in his profession and for decades, the old settlers of that community spoke with gratitude about the young doctor who came to their relief.

Two years later, he relocated to the village of Mt. Washington and in 1854 graduated from the Ohio Medical College. He was one of the founders of the Mt. Washington Academy, serving for years as secretary of the board of directors and by request, gave lectures on anatomy to advanced scholars. During the war, he was secretary of the Anderson Township Relief Society, of which Captain Benneville Kline was president. The Relief Society raised and dispensed large sums of money to alleviate the necessities of the families who had soldiers in the field.

When calls were made for physicians and medical stores of all kinds for the wounded and sick after the Battle of Pittsburgh Landing, the citizens of the township unanimously chose Dr. Bishop to furnish supplies for the two companies that had gone from this territory. Also known as the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Pittsburgh Landing took place from April 6 to April 7, 1862, and was one of the major early engagements of the Civil War (1861-65). The battle began when the Confederates launched a surprise attack on Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant in southwestern Tennessee. After initial successes, the Confederates were unable to hold their positions and were forced back, resulting in a Union victory. Both sides suffered heavy losses, with more than 23,000 total casualties, and the level of violence shocked North and South alike.

Dr. Bishop was elected to proceed to the scene of the late battle with the supplies and bring back the dead, sick and wounded that could be moved. By noon of the next day, the patriotic women of the township gathered and contributed a large quantity of provisions and other necessities that were placed in Dr. Bishop’s charge.

With these provisions, Dr. Bishop joined the medical staff of Dr. Comegys on board the Monarch which arrived at Pittsburgh Landing the Sunday after the battle. Dr. Bishop proceeded to first seek out those of his township requiring assistance; he dispensed supplies and medical aid. Within two weeks, he completed his labors and returned home with the dead and disabled soldiers. On his return, at a large assembly in Mt. Washington, a unanimous vote of thanks, the only compensation Dr. Bishop would accept, was given to the doctor for his patriotic and valuable services.

Dr. Bishop was a charter member of the Gerard Lodge in Newtown and served as its master for a dozen years. He was an elder in the Presbyterian Church in Batavia. In 1866, he was one of the organizers of the Clermont County Sunday School Union and he was a Sunday school teacher for more than twenty-five years. In 1867, Dr. Bishop moved to Mt. Carmel where he practiced medicine until 1872 before relocating to Batavia, Ohio. In 1879, Dr. Bishop was elected a representative from Clermont County to the sixty-fourth General Assembly of Ohio. He was on the committees of deaf and dumb, blind and imbecile asylums, medical colleges and societies. He was a member of the Legislature at the inauguration of President Garfield on March 4, 1881. After his move to Batavia, he was appointed government-examining surgeon under General Grant, to examine wounded and disabled soldiers who had applied for pensions. He also taught a class of convicts at the penitentiary while he was a member of the Legislature.

From his boyhood, he supported the cause of temperance and was a member of various temperance societies. He was married twice. His second wife, Louisa, was a daughter of one of the early pioneer families of Clermont County. She was described as “a very estimable lady” and was educated at the Female College in College Hill, Ohio. She was described as being “of retiring manners and one who looketh well to her household.” She accompanied Dr. Bishop on many of his travels. Dr. and Mrs. Bishop had two accomplished daughters, Bertha and Vesta, both of whom graduated from both the high school in Batavia and Oxford College.

He enjoyed “the confidence and esteem of all who knew him, and whether as physician, a member of society, or as a legislator, he has endeavored to discharge his whole duty with fidelity. He is justly sensitive of his honor and integrity and can never be swerved from the path of duty, nor engage in anything detrimental to what he esteems to be the interests of the people and good of society; hence, he was ever at his post in the Legislature, doing his whole duty and no more faithful, industrious and upright member could be found in the sixty-fourth General Assembly of Ohio. At the twenty-eighth annual meeting of the Clermont County Medical Society, held at Batavia, May 9th, 1880, Dr. Bishop was unanimously elected its president for the ensuing year, an honor only accorded the older and more distinguished practitioners.” Dr. Bishop was also one of the organizers of the Cincinnati and Eastern Narrow Gauge Railroad Company and was a large stock and bondholder in the corporation.

After he retired, he was described as someone who preferred the relaxation connected with managing his private affairs and the enjoyment of the surroundings of his home life, made pleasant by a family worthy of his name.

*For those of you who have delved into the history of Mt. Washington, you are probably familiar with the name Stephen Smalley. Mr. Smalley was a science teacher who also worked in WCET educational television beginning in 1959, making him an educational television pioneer. His interests were many and his knowledge was vast in the areas of science, history, and religion. He wrote many books about the history of Mt. Washington and Anderson. He was a meticulous researcher and I first became fascinated with Mt. Washington’s history by buying Mr. Smalley’s books. If you are interested, Stephen Smalley’s books can still be purchased at the Anderson Township Historical Society for a very nominal price. They are filled with fascinating stories and photographs.

Anderson Township Historical Society meetings are held monthly except January, July and August at Anderson Center, 7850 Five Mile Rd, Anderson Township on the first Wednesday at 7:30pm. The meetings consist of a historic program followed by refreshments. ATHS is a non-profit Ohio corporation.

Sources:

Dr. Leonard W. Bishop information from History of Hamilton County Ohio with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches. Compiled by Henry A. Ford, A.M. and Mrs. Kate B. Ford, L.A. William & Co., Publishers; The Biographical Cylopaedia and Portrait Gallery, Volume V, Western Biographical Publishing Company, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1881. Cholera information from

Daly, Walter J. “The Black Cholera Comes to the Central Valley of America in the 19th Century – 1832, 1849, and Later”, Walter J. Daly, Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 119, 2008.

Additional information source: Wikipedia