We have looked to Harriet Langdon, an early Mt. Washington resident, many times for recollections of what our community was like at its inception. We are fortunate that she recorded her memories in a book, From One Generation to Another, that was published for private distribution in 1906. The book was published to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the Langdon family’s arrival in Cincinnati from Vershire, Vermont.

We have looked to Harriet Langdon, an early Mt. Washington resident, many times for recollections of what our community was like at its inception. We are fortunate that she recorded her memories in a book, From One Generation to Another, that was published for private distribution in 1906. The book was published to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the Langdon family’s arrival in Cincinnati from Vershire, Vermont.

Harriet Landgon’s family were Methodists. The first church of this denomination that her family attended was in Madisonville. That church was built in 1801 near the intersection of today’s Red Bank and Brotherton Roads.

The Methodist Church was influential in shaping the course of American cultural development during the early 1800s. This was due in part to an explosion in membership which the church experienced after the War of 1812. The 1816 annual conference recorded 214,235 members and 695 traveling preachers, but by 1844, over one million people had joined the denomination and more than four thousand ministers rode American circuits. The Methodist Episcopal Church was the largest religious body in the United States from the 1820s through the 1840s.

Early American Methodist leaders condemned Negro bondage as a sin and in 1784 issued a statement which directly challenged slavery. Bishops Francis Asbury and Thomas Coke, with other preachers, lamented the development of slavery and attempted to outlaw slaveholding in the Methodist Episcopal Church, but many members and ministers of the denomination approved of slavery and defended its practice by the scriptures.

Slavery was simply not outlawed in the scriptures. The average Methodist was intensely concerned with his salvation, but many Methodists believed that it was possible to hold Negroes in subservience and enter heaven. Slave-holding church members reacted violently to the anti-slavery stand of the church. Eventually, Methodist leaders acquiesced, abandoning the declaration of 1784. The church conformed to the values of southern society, tolerating slaveholding by members of the denomination. This meant that the largest religious group in the United States sanctioned slavery until the General Conference of 1844.

Harriet explained that in the early 1800s there were few churches except in large cities. In the country, meetings were held in private homes and in barns during colder weather. In the summer, outdoor meetings were conducted in orchards and in the woods. Meetings were frequently held in Harriet’s family’s home and across the street at her Uncle Oliver’s home.

I did a little digging to find out about Harriet’s Uncle Oliver. He was born in Massachusetts in 1769 and was one of eight children. When Oliver came to Ohio in 1807, he initially built a log cabin which was known as Red Bank Station. It was a type of blockhouse to which settlers flocked for safety whenever there was a threatened Indian attack. Oliver received a poor education due to the limited schools available in that time. However, he loved books and spent any spare time reading when he wasn’t laboring on the family farm. Later in life, he built another house in which he spent the remainder of his days.

His home was the rendezvous for all the itinerant Methodist preachers who came along, all of whom commended him on his hospitality. There was also a small house on his farm which was used for school and church. Oliver was described as being “possessed of a humble and childlike disposition.” For over thirty years, he was a humble preacher of the gospel. He died in 1828. It was written that when he died, “the suffering poor lost a friend and benefactor. Few men, if any, who ever lived in his community were as pure in character and so generally beloved by all as he was.”

People came from Madisonville and all around the neighborhood to attend services at Harriet’s home and at Uncle Oliver’s home. Harriet recalled that her family’s kitchen was often filled with a band of earnest worshipers. The children were sent to her mother’s room for the duration of the meeting.

Circuit-riders were the primary instrument of the great expansion of Methodism during the first half of the 19th century. Circuit riders were clergy who were assigned to travel around specific geographic areas to minister to settlers and to organize congregations. About once each month, the traveling minister appeared on horseback.

This was not an occupation for the faint of heart. These ministers were known as “saddlebag preachers” because they traveled with few possessions, only what they could fit in their saddlebags. Church members were relied upon to provide ministers with food, clothing, shelter and other necessities because an itinerant minister’s salary seldom covered a year’s expenditures.

Being a traveling minister was likely to shorten one’s life. Over half of the first eight hundred ministers died before they reached the age of thirty! These ministers were vulnerable to illness, the hardship of constant travel in a time of primitive road conditions, exposure to weather, financial difficulties and loneliness. The itinerant endured hardship and physical suffering that demanded great patience and endurance. In the pursuit of his duty, the Methodist circuit-rider became a symbol of dedication. During the early nineteenth century, American citizens often described the severity of a storm by stating, “There’s no one out today but crows and Methodist preachers.”

In the early decades of traveling Methodist ministers, the denomination did not establish social or educational qualifications for ordination. Church leaders accepted every sincere man as a candidate for ministry. Itinerants from sixteen to over sixty years of age traveled the circuits. The church did not provide instruction for its preachers, so the circuit-rider devised his own means of education, learning through constant personal study and practice.

In their sermons, the preachers attacked deeply rooted sins such as drunkenness, adultery, pride, envy, self-will and bitterness. These sins were removed from the Christian’s heart when he surrendered to the love of God.

Many Methodist ministers spoke quite loudly during a sermon. There are several explanations for this form of speaking. Sometimes, the ministers wanted to draw a large crowd and shouted their message. When a gathering was extremely large, a minister often spoke to be heard by the entire audience. Some circuit-riders preached loudly to emphasize a topic. A few audiences did not appreciate a sermon preached in this manner and some members complained. A Methodist approached minister Joseph Travis after one service and exhorted him to have “more faith and less noise.”

Many Methodist circuit-riders were long winded. A sermon lasted for over two hours on numerous occasions. Some ministers became famous for the time they “held forth.” Peter Akers (1790-1886), an Illinois Methodist, preached from three to five hours on occasions. When he went to Lexington, Kentucky to preach, the congregation placed a time limit on his message.

Circuit-riders distributed printed materials to members of the denomination. They also sold books and pamphlets to many American citizens. It wasn’t unusual for printed sermons to have a larger distribution and readership than regional newspapers. In looking through old newspapers of the day, I found that sermons were often printed in the newspapers.

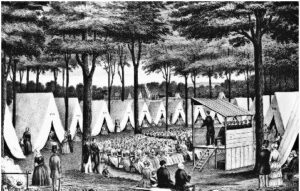

Camp meetings were also held in those days. Harriet recalled a visit to a camp meeting in the woods. The whole family went in a big covered wagon. Before their departure, Harriet’s father nailed down all the windows and made everything secure. Her mother prepared a chest full of provisions. Harriet felt her mother had overtaxed her strength in the effort since she became ill on the way to the meeting. The route lay through the river bottoms where the corn was growing high. The wagon had to ford the Miami River and travel up the steep hills beyond it. When they arrived at the campgrounds, they saw white tents gleaming among the trees.

Camp meetings were also held in those days. Harriet recalled a visit to a camp meeting in the woods. The whole family went in a big covered wagon. Before their departure, Harriet’s father nailed down all the windows and made everything secure. Her mother prepared a chest full of provisions. Harriet felt her mother had overtaxed her strength in the effort since she became ill on the way to the meeting. The route lay through the river bottoms where the corn was growing high. The wagon had to ford the Miami River and travel up the steep hills beyond it. When they arrived at the campgrounds, they saw white tents gleaming among the trees.

The Langdon family shared a tent with Mr. William Hart’s family. The tents were made of cloth and straw was thrown upon the ground for beds. The Langdon family’s experience of camp life was short because they only stayed one night. All through that night, the rain poured without ceasing. The children slept soundly on their straw beds, but their mother continued to feel unwell.

Had the Langdons been able to stay for the duration of the camp meeting, they likely would have experienced something like the following: A typical meeting began in a low-key, almost solemn way. A preacher gave a sermon of welcome and led a prayer for peace and community. This was followed by the singing of several hymns. Then there would be more sermons since ministers preached all day and night. At night, the camp was illuminated by candles and bonfires everywhere.

Over the days, the sermons grew increasingly sensational and impassioned and the excited response of the crowd grew more prolonged. By the second or third day, people were crying out during the sermons, shouting prayers, and bursting into loud lamentations. They began to grab their neighbors and desperately plead with them to repent. As the preachers ranted without letup, the crowd was driven into a kind of collective ecstasy. In the night, as the torches and bonfires flared around the meeting ground and the darkness of the trackless forests closed in, people behaved as if possessed by something new and unfathomable. As one minister wrote, “A strange supernatural power seemed to pervade the entire mass of mind there collected.”

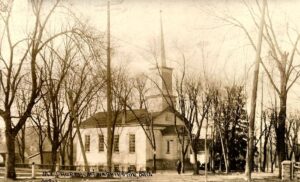

Over time, the population grew and more churches were built. Harriet’s family attended the Methodist Protestant Church in Mt. Washington. Until 1965, the church stood where Tower Optical now stands. The Methodist Protestant Church that was there moved to Corbly Road and is today’s Mt. Washington United Methodist Church. Harriet’s family also sometimes went to the Old Wesley Chapel in Cincinnati.

Over time, the population grew and more churches were built. Harriet’s family attended the Methodist Protestant Church in Mt. Washington. Until 1965, the church stood where Tower Optical now stands. The Methodist Protestant Church that was there moved to Corbly Road and is today’s Mt. Washington United Methodist Church. Harriet’s family also sometimes went to the Old Wesley Chapel in Cincinnati.

Harriet described the pulpit in the churches of these times. The pulpit was placed almost halfway to the ceiling and was reached by a stairway. There was a railing around the platform and pulpit with the entrance to the enclosure being through a small door or gate. As Harriet said, “The isolated and exalted position of the preacher caused the parishioners to look up to him in a very literal sense.”

Most churches had a mourner’s bench which was a very plain bench on which a person would sit to feel sorry for his sins, to repent, and to rededicate himself to God. After a sinner had mourned his spiritual condition, the pastor would come to the bench to comfort and pray for him. People believed that normal time was suspended when one was sitting on the mourner’s bench. While on the bench, one existed in sacred time in a sacred space. The bench was the place where earth met heaven and heaven met earth.

As Harriet related in her book, “It meant a lot in the early days to become a church member. It required great moral courage. The line of demarcation between the church and the world was clearly defined. A new convert often had a great deal to sacrifice – a manner of dress, the use of ornaments, and old associations. There were many new duties to be assumed, new obligations and responsibilities.” Harriet said that there was bigotry, prejudice, persecution and narrow-mindedness in the early days of the church. On the other hand, she recalled the strong piety and sturdy adherence to conviction characteristic of those primitive Christians.